Before we could write posts and send DMs of admiration on social media to our favorite artists, there was a thing called fan mail. Letters from fans of all genres would come from across the world, sharing how much idolized music superstars meant to them. They also expressed how a song changed their life and questioned the timeline of new music.

Beyond licking envelopes enclosed with messages for their adored artists, fans wrote notes to print publications expressing their opinions on cover stories about their beloved favs.

In the July 2001 issue of VIBE, a two-page spread was dedicated to fan mail reactions to Janet Jackson’s May cover story, which was written by Craig Seymour.

Jackson’s fan Tammy Gordon of San Antonio described the interview as “very enlightening.” She added, “It really showed her transition from wide-eyed and innocent to smart, strong, talented, sexy, free—just downright together and going on with life.”

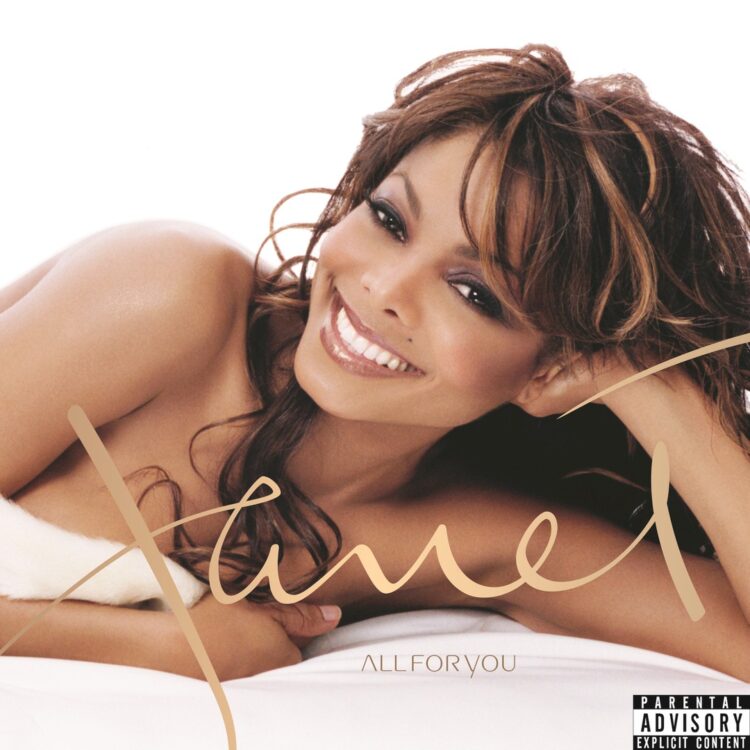

Jackson had moved on with her life, following a divorce from René Elizondo Jr. Nearly a year after her split, she released her seventh studio album, All for You. Some may assume the Carly Simon-assisted “Son of a Gun (I Betcha Think This Song Is About You)” was aimed at her former husband. Well, as Jackson sings, “Ha, ha, who, who,” too bad it was cleverly written in a way that anyone could be the suspect in question.

Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis had the range to make Jackson a torched heartbreak diva, but writing an album solely from a place of inherited hurt would have been too easy.

The same goes for selecting a single that contained the subdued tone of the already-crowned icon mulling over the missteps of the ended relationship. Jackson did what any newly single person may do after a recent breakup: hit the club, dance, and leave with whoever you like.

Despite already having a number-one Hot 100 single in her back pocket for the first time in the millennium with “Doesn’t Really Matter,” a single made for The Nutty Professor II: The Klumps soundtrack, the singalong track wasn’t exactly the song that screamed, “I’m available, take me now.” Instead, it was the title track taken from the follow-up to 1997’s The Velvet Rope.

Jackson has close ties to the ‘80s, having released four albums (Janet Jackson, Dream Street, Control and Rhythm Nation 1814) throughout the decade.

In 1980, two years before her self-titled debut album, Jackson was still a working actress, playing characters in sitcoms like A New Kind of Family and Different Strokes. That same year, the dance community was floored by “The Glow of Love,” a post-disco craze that swept across the nation like wildfire.

Luther Vandross’ urbane voice was responsible for leading this towering movement of cheery optimism on the easygoing hit from the European-American collective Change.

This was the same type of euphoric persona that Jackson wanted to project to her fans amid the media scrutiny of her nine-year marriage to Elizondo Jr. This is likely why she and her ever-tight wingmen Jam and Lewis chose the song for the external casing of Jackson’s radiant ode.

One more point for the axis of reimagining the Change’s ‘80s club-geared hit was Jam’s keen notice on how the traces of this evergreen sound and beaming attitude was also instrumental in ascending Jackson to the top of the dance-pop throne early in her career.

Jam told MTV in February 2001, “In the history of Janet, the records that are the happy records, that make people smile, have always traditionally been the more successful records.” He’s likely pointing to lighthearted, fun gems like “Escapade” and “When I Think About You,” both Billboard Hot 100 leaders in the ‘80s, respectively.

Right from the start, “All for You” transports fans back to the ‘80s when acid-washed jeans were all the rage, having a My Buddy doll was less creepy than today, and MTV played actual music videos all day.

The upbeat come-on is staged on opposite ends of the dance floor of a late-night spot, where Jackson has locked eyes with a timid romantic prospect. Her frothy and sunny tone here stirred as much interest in the pop sphere as popular teen sensations at the time, while her youthful appearance in the music video was akin to them, if not better.

Hearing the nostalgic beckon now, Jackson was doing everything imaginable to get this shy boy-toy, who is allusively well-endowed, to get him over to her side and back to her place for a bedroom rodeo. But she couldn’t blanket her celebrity status enough to break down the imposing walls of intimidation.

She tried to lessen his coyness on the second verse, singing, “Don’t try to be all clever, cute, or even sly / Don’t have to work that hard / Just be yourself and let that be your guide.”

The Dave Meyers-directed video opens with a shot of Jackson and a male passenger on a superficial train headed nowhere fast. At the next stop, Jackson, styled in trendy denim and a multi-colored halter top, joins a troop of female commuters on the railway platform to dance in unison.

The fashion and choreography evolve in other scenes like outside a 2D boardwalk and a resemblance of downtown Hollywood where a billboard of her showing her almost bare derrière is in lights. She spots the male transit once again in the club, getting a final wave in before she disappears in the night.

By the looks of it, the clean-cut specimen never found his way across the club and in the section of the smoking hot Jackson, but the pop phenom found herself immersed in acres of unrivaled accolades and success for “All for You.”

In March 2001, Jackson had the highest-debuting single (No. 14) on the Hot 100 since Billboard amended its rules for tracks without retail value to chart, thanks to airplay from an early leak in February.

Out the gate, the album’s title track had cross-format appeal, proving itself when it simultaneously controlled radio formats as diverse as pop, rhythmic and urban in one week. According to radio veteran Kevin McCabe, this was the best airplay move for a song of any kind, dubbing her as the Queen of Radio at the time.

Two weeks before retailers across the world stocked their shelves with the album All for You, the single unseated Crazy Town’s “Butterfly” from the Hot 100 hilltop, making it Jackson’s tenth chart-topper. It also headed other charts like the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks and the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Sales after tallying close to 30,000 in sales at core retailers.

Jackson enjoyed a jubilant seven-week run at the Hot 100 summit, sending her in the Billboard history books that year as the longest-running hit. She was the first solo female artist to lead the chart since Christina Aguilera’s “Come On Over Baby (All I Want Is You)” in October 2000.

Even more impressive, the album ruled atop the Billboard 200 after it sold over 605,000 copies in its first week. It logged her as the largest opening album sales of her illustrious career, as well runner-up, at the time, for the hugest start on the popular albums chart by a solo female artist. To top it all off, “All for You” won Best Dance Recording at the Grammy Awards in 2002.

A lightweight track like “All for You” may seem like a breeze for the top billing female pop-R&B acts from the time, but not many of them managed to recapture that stately compendium of upbeat, nostalgic dance-pop that has always been second nature to Jackson.

On “You,” Jackson proudly reversed the prescriptive gender stereotypes that were etched in stone from the beginning of time that men are expected to be forward in settings like a club, and women are predicted to be coy.

Though she is a magisterial pop force, Jackson’s position in music didn’t mean a strong Black woman like herself was aloof to men who don’t share the same tax bracket. Her status should not undermine her dating pursuits; she is still a woman who deserves and wants attention from different versions of men.

As she put it on “Someone to Call My Lover,” a hopeless romantic dance number and the LP’s second single, what makes a good man in her eyes is one that is “strong, smart, affectionate” and not “too shy.”

Going back to the subject of the title track, Jackson’s commanding style in sending out signals to a budding interest, regardless of his earning power, was adopted by fellow R&B counterparts. Brandy’s mild hit “Full Moon” cited Jackson’s observant tactics for scoping the room as she sighted an attractive club-goer.

Like Jackson’s waiting for an answer on her bashful potential’s alacrity, Cassie’s 2006 breakout hit “Me & U” found her awaited with pleasure to make a move following his green light. Mariah Carey’s Jermaine Dupri-featured track “Get Your Number” references components from Jackson’s “All for You”: the “can’t wait all day” attitude, intimating notoriety, and an ‘80s club sample.

In 2021, Jackson is in fifth place for the most number-one singles on the Hot 100 for a solo female artist, with “All for You” logged as her last major hit on this chart. While Damita Jo could have let her fresh divorce harden her heart and result in producing some sort of revenge album, she took a different approach, evidenced on the title track. She found a way to latch onto a familiar ‘80s sound and present its radiant optimism for tomorrow’s future on “All for You.”

Rereading the fan comments in the July issue of VIBE made me realize why Jackson chose sanguinity over melancholy. She didn’t just do it all for herself, she did it all for you — the fans.

Revisit Janet Jackson’s All for You album below.