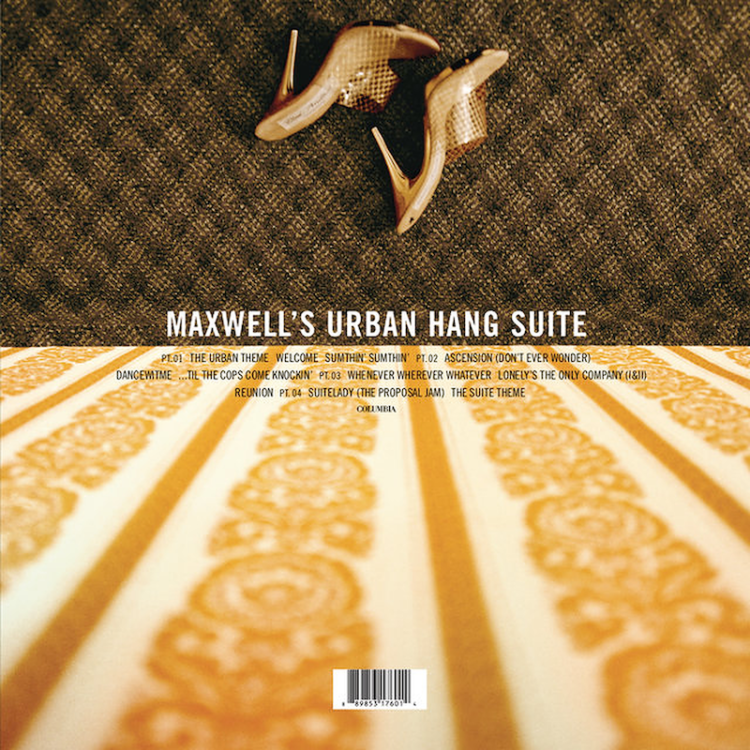

In 1996, a pair of nude mesh, stiletto mules, laid daintily on an almond diamond pattern carpet on Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite’s retro cover shot.

Instead of offering his early audience and curious music buyers a compelling still portrait of himself on the album’s frontal image, the ambitious future soul man used the fashionable heels as a small preview inside a bachelor pad connected to illicit love.

It made sense that Maxwell would use the shoes in a figurative style, associating them with an unnamed muse. The abandoned pumps casually implied a short romantic affair, ultimately supporting the love-adorned story in his debut opus.

Yet, the pure soul and unabashed fondness for a passing love Maxwell called forth on this supreme album are from his forebears’ smooth and seductive pedigree, namely, Marvin Gaye.

Urban Hang Suite picked up the common conceptual thread of Gaye’s music from the ’70s. It was Maxwell’s salute and tribute to the soul pioneer’s cinematic work.

“I was, and still to this day, very obsessed with Marvin Gaye’s approach to records,” Maxwell tells Rated R&B, as he namechecks many of the late icon’s most influential albums, such as What’s Going On and I Want You.

“He made records that felt like movies to me. I wanted to give myself a chance to conceptualize something in that way as a debut.”

During early studio sessions, Maxwell expressed his admiration for Gaye and other Black artists with Stuart Matthewman, a respected saxophonist and member of the legendary band Sade.

“He turned me on to some things I didn’t know about. Then I was saying things he didn’t know about. But we both loved Loose Ends and obviously Marvin [Gaye] and Al Green,” Matthewman recalls to Rated R&B.

Coincidentally, Urban Hang Suite arrived on April 2, 1996, which would have been Gaye’s 57th birthday. In every respect, the dawning of Maxwell’s first album and Gaye’s birth converges with the bearing of a new frontier of soul, neo-soul, that is.

Answering this destiny, Maxwell was determined to create a concept album that would pay respects to the many greats before him, allowing their influence to inform the music and a new generation of followers with an even higher purpose.

For Maxwell, it wasn’t about quick fame and immediate gratification. If the project didn’t succeed, he knew that “there was a rhyme and a reason and meaning and purpose behind it.”

“Regardless of how people accepted [Urban Hang Suite], I knew that I was creatively engineering something that would bring me satisfaction because there was no concept in anyone’s mind that a record like this would do anything — at all,” Maxwell notes.

One person that knew Maxwell had it in him to prevail was Mitchell Cohen, senior VP of A&R at Columbia Records. Cohen signed Maxwell to the label in 1994 after he caught wind in the New York streets about a young kid charming audiences in nightclubs like Nell’s.

Maxwell vividly recalls his first performance at the busy Manhattan joint, citing Spike Lee as an attendee. He also remembers hearing his suave, magisterial voice come through the microphone for the first time at soundcheck. “I was completely freaked out by the whole thing,” he says.

Having gone through that experience helped cease the school of butterflies racing through his belly about a promising future for him in music.

“It’s something I would have never wanted to do because I’ve seen how artists can be celebrated and denigrated and then celebrated again, and I’m quite sensitive,” Maxwell reveals. “I still have a little of that sensitivity. You want people to like you, but to do something with magnitude, you have to be willing to accept that some people won’t like you.”

View this post on Instagram

It’s a little hard to fathom that Maxwell released Urban Hang Suite at only 22, but he did. (He turned 23 in May 1996.) His old soul barred a confident and inviting coolness on even the most endearing songs, proving himself as an able balladeer.

There was a time when his intention for the album was unclear. “It wasn’t like everyone understood what I was trying to do. I can’t even say I understood what I was trying to do. I was feeding off the fact that I had a whole life that I had lived up to the very first record,” he recalls about how the journey to the album began.

But this didn’t mean that his idea for an album never existed. “It was always a thing for me; even in 1992, it was a thing I wanted to do. I had the title of the album. It was that sort of creative visualization where you have something you want to do in your mind, [but] the world hasn’t caught up with your wish,” Maxwell says about when he knew the album was forming.

His original wish was different, though. “Initially, I was just looking for a publishing deal. I thought, if I could just write songs for people, that’d be cool.”

Maxwell had plans to shop records to heroes like Earth, Wind & Fire. In previous interviews, he mentioned he wrote at least 300 songs in those days when his name ran across nightclub marquees. All the while, he continued to punch the clock at night at a local restaurant and moonlighted at other odd jobs to make ends meet.

Cohen had another vision for the young musician, which would give him free rein to steer his album from start to finish. It was a unique opportunity for such a new artist that Maxwell is still grateful for today.

“I was allowed just to make a record,” he says. “[Cohen] didn’t subscribe to the ideology that he was making an R&B or a Black album; he was just making a record. I was about telling a story — this thematic experience — on the album and hoping that I would be seen by people who looked like me.”

“…TIL THE COPS COME KNOCKIN'”

Producers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Peter Mokran (P.M.)

Writers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Hob David (DAVID)

“…Til the Cops Come Knockin’,” the carnal police report, soaked in unending sweat from Maxwell and his suga’s passionate lovemaking scene, was one of the first album tracks to be birthed by Maxwell. The Brooklyn native notes that it was recorded in 1991.

“A skeletal version of it was always there,” Maxwell says. “It was part of the reason why I think I got the deal.”

It also was the first song Maxwell wanted to go out as the lead single for Urban Hang Suite.

“When the album was done, I was very focused on that being the first thing to come out,” he says. “It’s so easy to put a record out that is obviously going to get more radio listens, but in respect to trying to keep the integrity of the conceptual aspect of the album, I was like, ‘Please, guys, ‘…Til the Cops Come Knockin’’’ really put that one out. I know it’s slow. I know it’s whatever it is, but we still have time for all those other records down the road.’”

“…Til the Cops” is also how Matthewman learned about Maxwell. He had received a demo tape of the song after Columbia Records executives approached him to lend a hand on Urban Hang Suite.

Matthewman describes the early version of the “…Til the Cops” as “pretty much as it was on the album.”

“It was kind of done. Maybe it wasn’t quite mixed, but it was all produced, and he sounded amazing to me,” he recalls.

Matthewman wasn’t quite sure why he was recruited to work with Maxwell since it appeared he was already headed in the right direction.

“I think maybe Maxwell had been asking about me because he loves Sade, and he loved the Love Deluxe album that had been out,” supposes Matthewman. “I think he had seen the live DVD, and obviously, he had found out that I had written for Sade, and it would be good [to collaborate].”

Though Columbia Records pushed Matthewman to be a part of Urban Hang Suite, his tight schedule made it easier for him not to give in to their persistence. All that would change when Karl Vanden Bossche, a percussionist for Sade, mentioned he had recently wrapped a session with the then-budding crooner.

Vanden Bossche went to visit Matthewman while in town and brought Maxwell along with him. Matthewman and Maxwell clicked. From there, the two began working on music together for the album.

“He came to where I was living at the time. I was in-between places. I didn’t even have a proper studio setup, just a couple of bits and pieces. But he came over, and we basically, over a few days, wrote three songs.”

WHENEVER WHEREVER WHATEVER

Producers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Stuart Matthewman

Writers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Stuart Matthewman

“Whenever Wherever Whatever” was one of the songs that Maxwell co-wrote with Matthewman. It abruptly invites heartache inside Maxwell’s suite, interrupting the album’s song cycle of a whirlwind romance. Gelled together by his floating head voice, glorious guitar picks, and cello hums, this supple lullaby documents Maxwell’s yearning for his departing interest, hoping that she keeps parts of him near and dear after leaves.

With the melody in mind for the song in 1994, Maxwell explains that he wanted to write from the softest place of his heart. “I think it’s so important that people write from a place of vulnerability, especially when you appear to be a person that should not have any insecurities or any vulnerabilities,” he expresses.

Matthewman adds, “We decided that we really didn’t want it to be a big ballad with the drums and the orchestra coming in and the brass section like most people would have done. We wanted to keep it really beautiful and simple.”

For many reasons, Maxwell kept his vision of a concept album and sessions for it a secret from label execs. “I’ve learned that you work best by not letting people know what you’re doing really and how you’re doing it because when people know, they can actually put a lot of expectation on top of the work,” Maxwell says about writing and recording discreetly.

“A lot of my friends didn’t know that I was into making music. They realized it after the fact. I always keep those things quiet because maybe it’s my insecurity. Maybe it’s my being afraid that I wasn’t going to make it. So if you don’t speak about it and do it and it doesn’t do anything, no one really knew. If it does something and everyone knows. Luckily for me, my relationship with Mitchell was so strong that I was allowed just to make these records and then, later on, sequence them the way that I wanted to.”

One of the things that Maxwell was pleased about was the embrace he received from two Motown architects: guitar legend Melvin “Wah-Wah Watson” Ragin and the acclaimed songwriter and producer Leon Ware. Both worked with Gaye on albums that Maxwell regarded, giving him more reasons to be in total awe in their presence.

Maxwell remembers how surprised both Watson and Ware were when they received his request to work on his album. Maxwell says, “They didn’t understand it. People thought, ‘Oh, it’s a young man’s game.’ That’s kind of how it usually is in most of the entertainment industry. I was so happy to be that kid who could meet them, be accepted by them and create with them because, for me, the traditional soul music is ageless. It’s a timeless thing. Like, literally, all music is black music — it just is. I’m sorry if it offends anyone.”

SUMTHIN’ SUMTHIN’

Producer: Maxwell (MUZSE)

Writers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Leon Ware

With songwriting assistance from the esteemed Ware, Maxwell put pen to paper and came up with “Sumthin’ Sumthin,’”Urban Hang Suite’s third single. It was a mellow serenade where the gracious vocalist slaps on his urbane charm, asking his woman of interest, with the utmost respect, for permission to take her out and kick it any way she likes.

Repeated lyrics like “If it’s cool” signal that Maxwell recognizes that Black women have agency over their decision-making, especially when accepting or refusing a date offer. He also pledges his allegiance to the anatomy of Black women, citing the beauty in their skin tones and innate swag in descriptive lines like “lose myself inside her ebony,” “flavor with a cocoa kinda flow,” and “honey, dew sugar chocolate dumpling.”

As he reflects on his time with Ware, who passed away in 2017, Maxwell remains thankful that he was able to cross paths with such an iconic contributor to soul music. He holds his last talk with Ware close to him as it was the day before he transitioned.

“I was happy to be able to speak to him and thank him for impacting my life even before meeting and working with him,” Maxwell says. “I’m just grateful that I’ve approached my creative path with purpose and with meaning — not trends, not what’s of the moment, or what’s going to secure me, but what was meant to happen based on the things that I cherished as a kid growing up.”

ASCENSION (DON’T EVER WONDER)

Producer: Maxwell (MUZSE)

Writers: Maxwell (MUZSE) and Itaal Shur

Matthewman’s participation wasn’t limited to just three songs. Maxwell granted him clearance to blow his sax and wield his guitar on other songs like “Ascension (Don’t Ever Wonder),” the first radio-targeted moment from the album. It was even bigger that Matthewman was joining a record where he was able to share the field with one of his idols: Wah Wah Watson.

“If you have a bunch of different producers, working with an artist on one album, they don’t normally play on each other’s tracks,” Matthewman says. “[But] he was like a massive influence on me when we first started with Sade, so I was like, ‘Fuck yeah, I want to be involved with that.’”

“Ascension” demonstrates the range of Maxwell’s elastic voice, showing off a multi-octave ululation in the opening notes. It’s almost like the sturdy bass, shrieking wah pedal, and programmed drums placed underneath his melodious voice gave him even greater wings to soar.

Maxwell had every reason to take flight here, as he lifted up his extraordinary muse on a deserving pedestal for exciting his mind, body, and soul in every way imaginable.

A song like “Ascension” is the perfect confidence booster to women everywhere, particularly Black women, who have second-guessed their position in a courtship with a respective partner.

Here, Maxwell clears his lover’s doubts about her place in his life and even her own, elevating her in the power of reassurance on all levels. Towards the end of the song, he reverts to his vulnerability again, citing that “without you, there’s no me.”

Like many other R&B songs, programmed music, like drums, were significant factors in forming a tune, especially in the ‘90s. But Matthewman explains what was clearly different between songs for other artists and those of Maxwell on this album.

“They didn’t have a lot of musicality with it,” Matthewman notes. “I mean, it was great, and we loved it, but what Maxwell brought [and] having people like me and Wah Wah Watson and Federico [Pena], the keyboard player, was having musicality around the vocals.”

He continues, “So, you would have little guitar bits and another instrumentation like sax that a lot of other people weren’t doing as much. That’s something we had always done for Sade, but that thing that I thought made him and obviously, D’Angelo and Erykah Badu and other artists stand out, which was the musicality as well as the programmed stuff.”

THE ELEVATOR TO SUCCESS

The world may have first heard Maxwell’s impactful and understated debut album in 1996, but its shelf life had existed one year earlier.

In August 1995, Columbia Records launched its Black music division headed by executive VP Michael Mauldin, a former artist manager, and Jermaine Dupri’s father. The department was designed to focus on the growing demand for R&B music.

More reorganization shakeups occurred, causing an even greater delay in Urban Hang Suite’s release date. There were even reports that claimed Columbia Records was hesitant to release the album, for fear of possible commercial failure.

“We’d done it, you know? Mixed it, done everything, and they didn’t put it out,” says Matthewman. “I don’t know if they were nervous about it or worried about radio, but it must’ve been incredibly frustrating for Maxwell. It was a shame that they sat on it for so long.”

Maxwell understood the business and politics behind it, though. “I think it’s tough for people to understand that someone that young could be aware of what they wanted to do,” Maxwell explains about his album being shelved for a year. “I get it now in hindsight as a 47-year-old man; why should they have trusted someone so young, who had never done it before, to know what he wanted?”

He applauds Columbia Records for their decision. He believes that they wanted to “do the right thing by me or the right thing by the other artists who were signed at the time.” He even saw it as a positive for the album as a whole.

“It was a great thing that it took a year for it to come out. I think people just knew I cared about all of it so much: the music, the mix, where we were going to record it, the visuals, the whole thing. I got to tweak it a little bit more. I [also] got to look at what was happening [in the music landscape].

I can’t say that I wasn’t disappointed and that I wasn’t fearful that this was maybe the beginning of the end, but I remained faithful about what I was trying to do. I think that things ended up happening the way that they were meant to. I’m grateful about that.”

It took nearly five months for Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite to reach the top 10 on the Billboard Top R&B Albums chart after debuting at No. 39 in April 1996.

Its second wind had a lot to do with the winning results of “Acesenion (Don’t Ever Wonder),” which was high up on both urban and R&B radio stations. On Billboard, the song ranked at No. 7 on the former airplay chart and No. 2 on the latter.

Sometime shortly thereafter, “Sumthin’ Sumthin'” marked Maxwell’s second top 10 single on the Billboard Adult R&B side, making it to No. 10.

Maxwell realizes the frenzy in radio spins and accomplishments on Billboard and elsewhere for both songs were due to the investment a radio veteran put into the cult staple, “…Til the Cops Come Knockin’.”

“I just want to shout out Cynthia Johnson, CJ, the first Black radio person, to understand this record and really explain to all those radio stations at the time why it was going to be important to play me [and] play the record,” Maxwell praises.

He also is indebted to early listeners who discovered him through radio and word of mouth and accepted what parts of past soul music he brought to the present and the soon-to-be future. “It was the people that had the last word — and that was the point,” Maxwell declares.

“The point was to let them be the judge and jury of what was being done creatively as opposed to knocking them over the head with, ‘This is what’s going to be great. This is the next whatever.'”

Although publications like VIBE were dubbing Maxwell the second coming of Prince as early as 1993, he again hailed Columbia Records for not overexaggerating his looming arrival.

“[They] were very smart at allowing that evolution to occur without beating anyone over the head about me being the next whatever the hell people wanted me to be,” he says.

All things considered, Maxwell was elated that his persistence and drive had moved mountains for him, but he knew, too, that his salient impact would forever change the way he was viewed as an artist. Maxwell says, “As much as I was excited about it, I knew that I would be typecast. I knew that all of a sudden, this thing that wasn’t obvious, that’s all of a sudden becoming kind of mainstream and understandable, that I was going to be held to the expectation of another version of this.”

This is precisely why, as evidenced in Rated R&B’s 20th-anniversary Embrya piece in 2018, Maxwell “sonically flanked in the opposite direction” with his experimental follow-up. “That was absolutely on purpose,” Maxwell explains. “Not to spite what I did in the debut, but to extend the hopeful possibility of being a more evolved creative person is what I wanted to do as an artist.”

THE NOW

Maxwell was in good spirits in the days leading up to the 25th anniversary of Urban Hang Suite. His smooth and kind speaking voice was rattled with excitement. It’s probably because he was amped to take to the stage at the 52nd NAACP Image Awards to celebrate this masterpiece, a likely cause in new births the following year of its release.

But, after listening back to our conversation, I can deduce Maxwell’s enthusiasm was sourced by the many scientists it took to make Urban Hang Suite a live and breathing entity.

At the beginning of our phone call, Maxwell took a moment to pause and acknowledge the “great cast of collaborators on this [album]” who each “were right in step with what we were ultimately trying to do.” He does it a few more times throughout the call duration as he fielded other questions, proving that his respect for the long list of guests wasn’t for formality but that it was sincere and genuine.

Maxwell commends his studio accomplices again when asked what about himself does he hear about himself on the album 25 years later that makes him most proud.

“We were such a diverse group of people,” Maxwell notes. “We weren’t trying to be diverse — it was just what I had available to me. It wasn’t like this marketed concept of how can we bring everyone in and look like we’re showing a healthy snapshot of what the world needs. We were just kind of reflecting the world and we weren’t even trying, it was just like, ‘This is the world.’ And I’m just grateful for that more than anything.”

Inclusion is also a part of Maxwell’s appreciation for his sustainability. “I see the memories of a young man not being sure if he’d be included in the tradition of soul and R&B,” Maxwell reflects, who is of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent.

“I’m not from the South. I would be criticized that I’m not really Black to people. People would literally say this. But to be able, 25 years later, tour in the Carolinas; Jacksonville, Florida; Little Rock, Arkansas; and see a full crowd out there, that included me, is what I’m most grateful for.”

Compared to albums or projects released today, Maxwell doesn’t quite know if Urban Hang Suite could exist as a conceptual body of work.

“Albums are not seen as albums anymore,” he points out. “It’s just what’s the best song or what’s the song that’s getting the most streams. And pretty much, you don’t really have to put an album out. You can just put one song a day or one song a week because that’s the barometer in which people view as being successful enough.”

He concludes, “I’m cool with all of it; it is what it is. It’s an evolution of the way people listen to music, but I’m just so happy that I was born in 1973, and I put out that album in 1996, and I got to experience all of that analog stuff that I loved and studied as a kid.”

Revisit Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite below.